Jump to Introduction & Chronology

Jump back to Previous: "A New Vision of the Mind" - Part 2

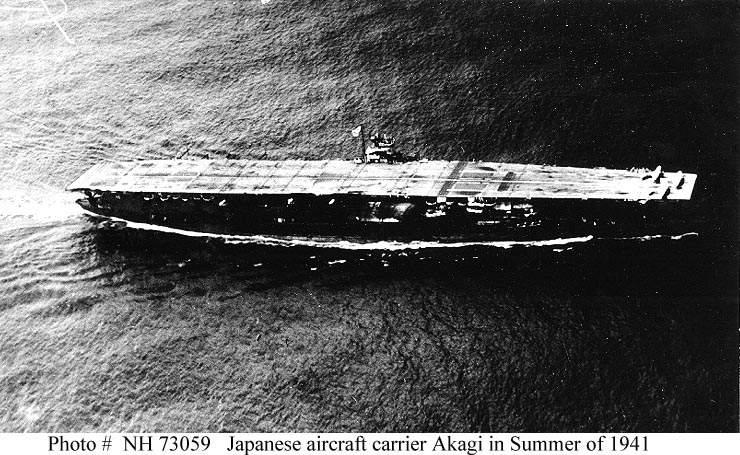

Lady Lex, Sister Sara, Kaga, and Akagi

WW1 aircraft carrier development

Aircraft carrier development didn’t get very far during the Great War. The U.K. Royal navy employed a few crude aircraft carriers later in the war to give them better reconnaissance capability -- a response to the fleet’s inability to keep track of the German fleet at the Battle of Jutland -- and also to provide some defense against zeppelins and the few primitive bombers the Germans sent to attack the fleet at sea. This wasn’t much, but they had at least established that planes could operate from ships and that they could be useful to the fleet.

After the war, both the American and Japanese navies (each originally modeled on the Royal Navy) decided naval aviation was something they needed to look into. They both decided to use a small aircraft carrier as a way to get their feet wet. The U.S. Navy spared every expense by simply converting an old collier into a test-bed for the warfare of the future. The U.S.S. Langley (CV-1) (commissioned in 1922) had one elevator to move planes between hanger and deck and two catapults to help get planes into the air. (She also had a “house” for carrier pigeons which were, very briefly, used to carry messages between planes and ship.) The Langley served in a training role until 1936 when she was converted into a seaplane carrier. In February 1942, during WW2, she was damaged by air attack after delivering aircraft to the then Dutch East Indies and finally scuttled.

The Japanese took the other option: The Hosho was the first ship to be designed and built (and commissioned in 1922) as an aircraft carrier. She was small but included features that wouldn’t be standard on aircraft carriers until the jet age -- catapults for launching planes and a system of mirrors and lights to assist planes in landing. Not only did the Japanese use the Hosho to gain their first experience with naval aviation, but she remained in service throughout the Pacific War. Most of the time she was used for training in home waters, but she sailed with the main battleship force for the Battle of Midway, to provide the same services to that fleet that the first carriers had provided for the Royal Navy’s Home Fleet during the Great War. The Japanese more than got their money’s worth from their investment in the Hosho.

Naval building and treaty

Immediately after the conclusion of the Great War, the U.S., Japan, and the U.K. started a naval arms race that had them all building battleships and battlecruisers in great numbers. Amazingly, many people recognized the stupidity of this, and in 1922 these nations (plus France and Italy) agreed to stop the construction race and even to remove many older ships from their fleets. (See Washington Naval Treaty.) The U.S. kept three new battleships and Japan kept two. Each nation was also allowed to convert two of the new battlecruisers then under construction to aircraft carriers. (Battlecruisers were similar in size to battleships but faster.)

On ship names

Until the end of World War 2 the U.S. Navy had a sensible approach to naming its ships. Battleships were named after states. Cruisers were named after cities. Destroyers were named after people -- almost always naval officers. Faced with building its first battlecruisers, the Navy went with naming them after famous U.S. battles so the first two hulls were named Lexington and Saratoga. After the Washington Naval Treaty stopped construction on these ships and they were converted to aircraft carriers, the original names were kept because seamen are very suspicious about changing a ship’s name -- it’s supposed to be unlucky. (Until after the war, U.S. aircraft carriers were named after either famous Navy ships or U.S. battles. It’s interesting to speculate what the Navy would have done if the example of their first two real aircraft carriers hadn’t pointed the way toward this dual naming convention. During the war there was only one exception to these rules, CV-38 was named Shangri-la. Here’s the explanation from Wiki, “The naming of the ship was a radical departure from the general practice of the time, which was to name aircraft carriers after battles or previous US Navy ships. After the Doolittle Raid, launched from the Hornet, President Roosevelt answered a reporter's question by saying that the raid had been launched from "Shangri-La", the fictional faraway land of the James Hilton novel Lost Horizon.” Right after the war President Truman approved naming one of the new, larger, Midway-class carriers after Franklin D. Roosevelt and since then, an increasing number of supercarriers have been named for politicians.)

In the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) the conventions were different. Battleships were named after provinces (or alternate names for Japan), cruisers after rivers or mountains, aircraft carriers... the mysteriously translated Wiki entry on this subject says “special names.” For our purposes, Kaga is a province and Akagi is a volcano.

The conversion

Amagi had originally been the intended battlecruiser twin of the Akagi but her hull was so damaged by the 1923 Great Kanto Earthquake that they had to substitute the battleship Kaga. This was not a small matter as the IJN liked to pair up similar ships to serve together. The Akagi would always be limited by the slower speed of the Kaga and, in time, so would the Kido Butai, the carrier striking force that attacked Pearl Harbor and that was, for a matter of months in late 1941 and early 1942 the most powerful naval force the world had ever seen.

It is important to realize how early this was in the development of naval aviation and aircraft carrier design. Many decisions and features we take for granted today were a great mystery at the time. Naval officers who had grown up on battleships were quick to see the vulnerability of an aircraft carrier at night, in bad weather, or when her planes were either off on a mission or destroyed. It was considered simple common sense to provide these ships with an alternative striking capability in the form of cruiser type 8” guns. Three of our four ships would sink with these guns still aboard (Saratoga would, while under repair at Pearl Harbor, give up her four twin turrets for the defense of Oahu at a time when Americans anticipated additional attacks there and even in California.)

Flying-off decks, islands, and funnels

At this time, naval aircraft were small, light, biplanes which required very little deck to take to the air. The British had hit on the concept of the flying-off deck and the Japanese adopted it with enthusiasm. The flying-off deck was really ingenious, instead of lifting aircraft to the main deck with an elevator, if you opened up the hanger at the bow you could fly the plane directly out of the hanger. Kaga and Akagi had two levels of hanger so they had not one (like the Brits) but two flying-off decks.

| Akagi with two flying off decks and no island |

Worried about turbulence on the main deck as the little biplanes landed, the Japanese went with a flush deck with no superstructure (island or funnels) rising above the deck. There is a wonderful steam-punk look to these ships as they were originally constructed.

By the mid 1930s aircraft had grown larger and heavier making the flying-off decks (and the resulting reduction in hangar space) increasingly problematic. Both ships were rebuilt with a number of improvements (and fewer cruiser guns) but the most obvious changes were flight decks that extended the full length and width of the ships and small islands for directing air operations but, just to see if it might make a difference Akagi’s island was placed on the port (or left) side while Kaga’s was on the starboard side like every other carrier in history except the Hiryu. Mostly this just made it much easier to identify Akagi and Hiryu.

The U.S. Navy Lexington-class ships avoided most of this, charming, exploration of the new genre. They were commissioned with full flight decks, islands and normal funnels -- actually they had enormous islands with their cruiser turrets taking up deck space fore and aft. The only obvious alteration made before the war was to slightly extend and square-off the flight deck at the bow. In fact, not only did these ships look exactly like the mature aircraft carriers of the supercarrier age, because of their hurricane bows (the hangar deck was not open to the air -- and sea -- as was the case in every other U.S.N and I.J.N. carrier of the period, except for the short lived Taiho.)

| Lexington as built. |

_at_anchor_1938.jpg) |

| Lexington three years before war. |

USS Lexington (CV-2) - "Lady Lex"

US ships have "official" nicknames in addition to the ship name. The USS Lexington, designated CV-2, was known to her crews as "Lady Lex". Subsequent Lexingtons in the USN would have different nicknames.

While battlecruisers had greater speed, their greater length, compared to battleships, meant that they were less maneuverable. On 11 January 1942 Saratoga was unable to evade a submarine torpedo and was severely damaged. Lexington was similarly disabled by torpedoes launched by aircraft during the Battle of the Coral Sea. (She was later sunk by five U.S. torpedoes after her crew was removed.)

While battlecruisers had greater speed, their greater length, compared to battleships, meant that they were less maneuverable. On 11 January 1942 Saratoga was unable to evade a submarine torpedo and was severely damaged. Lexington was similarly disabled by torpedoes launched by aircraft during the Battle of the Coral Sea. (She was later sunk by five U.S. torpedoes after her crew was removed.)

Kaga and Akagi

The Kaga and Akagi took part in the Pearl Harbor raid and in most of the major actions during the first six months of the Pacific War, when almost everything went the Japanese way. They even successfully evaded the few torpedoes launched by the obsolescent U.S. torpedo bombers at the Battle of Midway, but were then destroyed by bombs dropped by dive bombers from Enterprise and Yorktown.

USS Saratoga (CV-3) - "Sister Sara"

Twice disabled by submarine torpedoes, the Saratoga survived the war only to be sunk during atomic bomb tests following World War 2.

Epilog

The USS Lexington designated CV-2 was sunk on 8 May 1942. A new USS Lexington designated CV-16, and nicknamed “The Blue Ghost,” (an Essex-class carrier) was commissioned 17 February 1943 -- that’s a little over nine months later. That ship, not quite as heavy but improved in almost every way, fought in all the crucial battles of 1944 and went on to serve the U.S. Navy in one role or another until 1991, giving her a 48 year career. She is currently a museum ship at Corpus Christi, Texas.

Here is a documentary on aircraft carrier development.

Here is a documentary on aircraft carrier development.

Jump to Next: Faust... More than you bargained for

No comments:

Post a Comment